Copyright 2019 Robert Clark

This Aug. 28th tweet from Elon Musk surprised many when it asserted a 20km altitude Starship test hop in October and an orbital flight “shortly thereafter”:

https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1166860032052539392?s=21

https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1166860032052539392?s=21

That was surprising because, it is taken, that an orbital flight will require the Super Heavy booster stage. The problem is the Super Heavy is to have 35 Raptor engines. At current production rates it’s not likely you could have 35 Raptor engines for the SH and 6 Raptors for the Starship by the end of, say, October.

The “Everyday Astronaut” who usually has good info on the progress of SpaceX suggests as of Aug. 25th, only the 7th and 8th Raptors have been produced and he estimates a production rate of one Raptor per 2 weeks:

https://twitter.com/Erdayastronaut/status/1165630118603251712?s=20

https://twitter.com/Erdayastronaut/status/1165630118603251712?s=20

So some began to speculate, again, that at least for the initial test flights the Starship might be flown to orbit as an SSTO. But that’s OK. SSTO is not after all a four-letter word. Elon has said the Starship technically could be SSTO but not reusably as not having enough payload for adding thermal protection systems and landing fuel.

However, it is important to keep in mind the first test flights will not have the passenger quarters for the full operational Starship so will have a quite a bit lighter dry mass. For the first test flights it will more closely resemble the tanker version of the BFR upper stage. Elon has said that a stripped down Starship with no payload fairing and only three Raptor engines will have a dry mass of only 40 tons:

Having only 3 Raptors would work for the application mentioned in that tweet as upper stages commonly have lower thrust than their gross weight, as they don’t have to lift off from ground.

The test version of the Starship to only do the 20 km test hop is supposed to only use three engines, with reduced propellant load. So we can get an idea how accurate that dry mass of only 40 tons is for a 3 engined Starship-version with no passenger quarters in this case as the first test vehicle, if Elon releases the dry mass for it, which is open to doubt.

The Raptor engine might have a mass of 1 ton based on its high estimated T/W ratio and thrust ratings. So adding 3 additional Raptors to have 6 Raptors as planned for the full Starship might only have a dry weight of 43 tons. You would have to add the weight of the fairing but since the fairing is ejected once reaching near vacuum and well before attaining orbit, this should subtract only a proportionally small amount from the payload.

But 6 Raptors at 200 ton sea level thrust each would just barely be able to lift off a 1,200 ton BFR upper stage. You might have to reduce the propellant load somewhat to get a better liftoff T/W ratio. With a vacuum Isp of 356s vacuum Isp and 334s sea level Isp you would still be able to reach orbit with significant payload as long as the propellant is reduced by a proportionally small amount. _______________________________________________________________

That’s the argument why the first test flights might be SSTO. However, it still is possible that the Super Heavy booster will be used. This may have been aspirational on his part, but Elon tweeted back in May they want to ramp up Raptor production to one every three days by the Summer:

If they have reached this production level, then over the next 60 days to the end of October you could have 20 additional Raptors produced. This still will not be enough for the full 41 engined two-staged BFR. But there has been suggestion the initial test Super Heavy might only be given 20 Raptors:

https://twitter.com/rdstrick777/status/1167458646579564544?s=21

https://twitter.com/rdstrick777/status/1167458646579564544?s=21

With the 8 Raptors already produced, this would be enough using 6 or 3 Raptors on the upper stage. This could not lift the full propellant loads of the Super Heavy and Starship. So also in this case you would have one or both stages with reduced propellant loads.

But this introduces additional problems for reusability in regards to this test flight because such large amounts of propellant need to be kept on reserve for returning the first stage booster to the launch site.

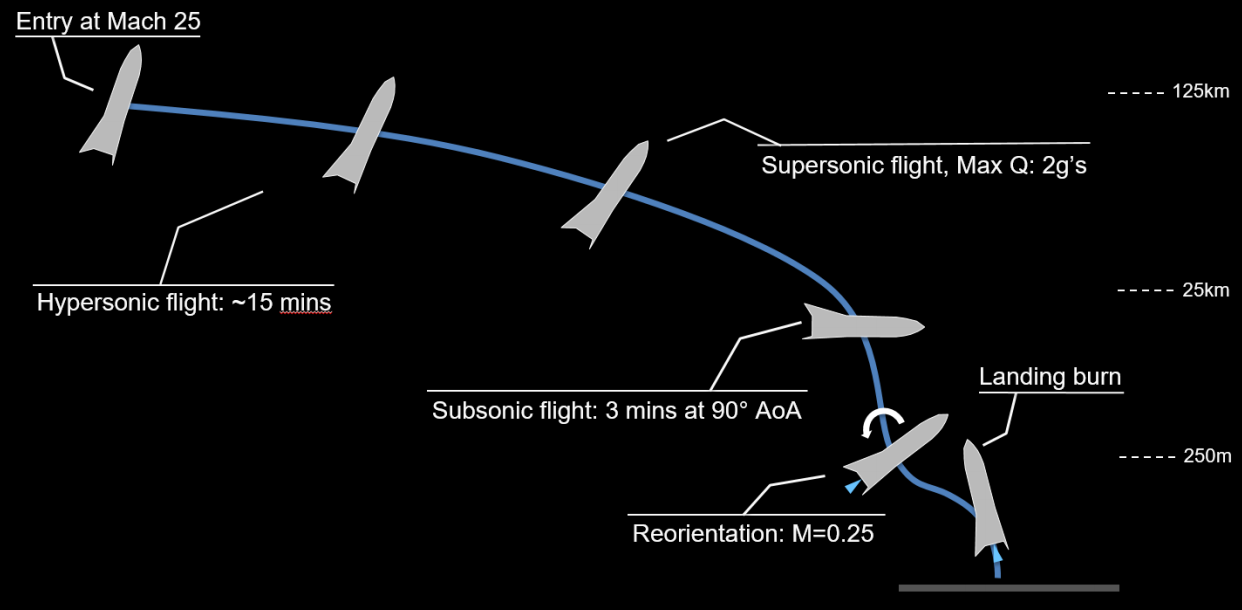

Then actually the SSTO test might be better because for reusability of a returning upper stage only a proportionally small amount of propellant needs to be kept on reserve to cancel out ca. Mach 0.25 = 80 m/s on landing:

Bob Clark