Copyright 2017 Robert Clark

Introduction.

In the blog post

"Orbital rockets are now easy", I argued that with altitude compensation, liquid-fueled orbital rockets become within the capabilities of most university undergraduate labs.

Here I'll argue solid-fuel rockets can also be built by amateurs to reach orbital space.

I was impressed by this university teams launch to 144,000 feet of a suborbital solid-fuel rocket:

USC Rocket Propulsion Laboratory Breaks Record.

Amy Blumenthal | March 16, 2017

Student-run RPL launches rocket of own design to 144,000 feet.

LAUNCH OF FATHOM II ON MARCH 4, 2017. AT 144,00 FT FATHOM II WAS THE HIGHEST ALTITUDE FOR A ROCKET ENTIRELY DESIGNED AND MANUFACTURED BY STUDENTS

https://viterbischool.usc.edu/news/2017/03/usc-rocket-propulsion-laboratory-breaks-record/

However, using essentially "off-the-shelf" components, you can get a 3-stage solid rocket of comparable size to actually reach

orbit. Moreover, I was surprised to see after running a launch simulation program that you don't even need altitude compensation to accomplish it.

By essentially off-the shelf, you could use solid-rocket motors sold to amateurs but with an addition of a lightweight carbon-composite casing that amateurs such as the USC team already have been making themselves for their own rockets.

You would have Cesaroni Technology, or other solid motor manufacturer, make their motors with only a thin aluminum case, not meant to hold the full combustion chamber pressures. The amateurs would then make the carbon composite case rated for the full combustion chamber pressure.

Cesaroni also makes commercial sounding rockets with carbon composite casings but this is likely to be more expensive than if the amateurs make it themselves.

Specifications.

This motor by Cesaroni Technology,

or similar motors by other manufacturers, could form the basis of the orbital rocket:

This motor though only has a mass ratio of about 2.5 to 1, adequate for amateurs doing

high power rocketry test flights, but not for an orbital rocket. However, you can save about half of the weight of the aluminum casing used by replacing it by carbon composite.

Cesaroni was able to do this for the suborbital rocket SpaceLoft they constructed for UP Aerospace, Inc.:

CTI rocket motor successfully powers the launch carrying the ashes of astronaut and James Doohan - April 30, 2007.

On April 28th, a Spaceloft™XL rocket successfully completed a round-trip space flight launched from Spaceport America. This rocket was developed by UP Aerospace Inc. of Hartford, Conn. The rocket carried a wide variety of experiments and payloads, which included the cremated remains of Star Trek's "Scotty", James Doohan and NASA astronaut and pioneer Gordon Cooper. In addition, the cremated remains of more than 200 people from all walks of life were onboard. Also flown into space on the SL-2 Mission were dozens of student experiments from elementary schools to high schools to universities - from across America and worldwide - as well as innovative commercial payloads.

The flight was a successful demonstration of the rocket motor developed and built by Cesaroni Technology Incoporated (CTI). CTI started the design process in September of 2005. CTI specializes in low cost propulsion systems for military and space applications and used its experience to develop an affordable, reliable propulsion system for the rocket. The motor has a carbon fiber composite case and a monolithic solid propellant grain that is bonded to the casing.

Watch the post-launch coverage as carried by local television station KRQE here (9 Mb)

Watch the launch as carried by the BBC here (1 Mb)

Watch pre-launch coverage as carried by CTV Toronto here (9 Mb)

Watch pre-launch coverage as carried by CBC Toronto here (9 Mb)

Technical data for the UPA-264-C rocket motor

So we'll assume the Cesaroni Pro150 can get a 0.8 propellant fraction by using carbon composite casing. We'll round off the propellant mass to 20 kg, and take the dry mass as 5 kg. We'll take this as the third stage of our rocket.

For the lower stages, the size of stages commonly are in the range of 3 to 5 times larger than the succeeding stage. We'll take the second stage as 4 times larger than the third stage at a 80 kg propellant weight and 20 kg dry weight. For the first we'll take it as larger by an additional factor of 4 to a 320 kg propellant weight and 80 kg dry weight.

Now for the specific impulses for the stages. This commercial solid motor has a similar sea level Isp as the Cesaroni solid rocket motor Pro150:

Star 37.

Thiokol solid rocket engine. Total impulse 161,512 kgf-sec. Motor propellant mass fraction 0.899. First flight 1963. Solid propellant rocket stage. Burner II was a launch vehicle upper stage developed by Boeing for the Air Force Space Systems Division. It was the first solid-fuel upper stage with full control and guidance capability developed for general space applications.

AKA: Burner 2;TE-M-364-1. Status: First flight 1963. Number: 180 . Thrust: 43.50 kN (9,779 lbf). Gross mass: 621 kg (1,369 lb). Unfuelled mass: 63 kg (138 lb).

Specific impulse: 260 s. Specific impulse sea level: 220 s. Burn time: 42 s. Height: 0.84 m (2.75 ft). Diameter: 0.66 m (2.16 ft).

Thrust (sl): 33.600 kN (7,554 lbf). Thrust (sl): 3,428 kgf.

http://www.astronautix.com/s/star37.html

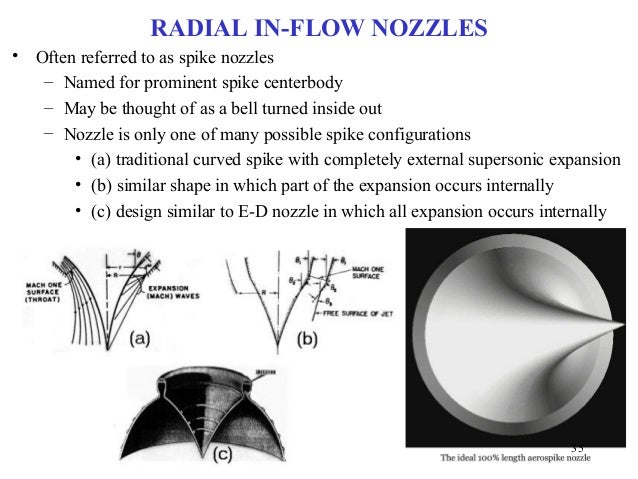

So we'll estimate the vacuum Isp of the Cesaroni Pro150 to be in the Star 37's range of 260 s. However, rocket stages can get higher vacuum Isp's by using longer nozzles. A 285 s Isp is not uncommon for solid rockets motors with vacuum optimized nozzles,

such as the Star 48.

So we'll take the Isp for the second and third stage as 285 s.

For the thrust, we'll take the thrust of the third stage as the same as the Pro150 of 8 N, and assume the thrust for the second and first stage scale according to their size so to 32 N and 128 N, respectively.

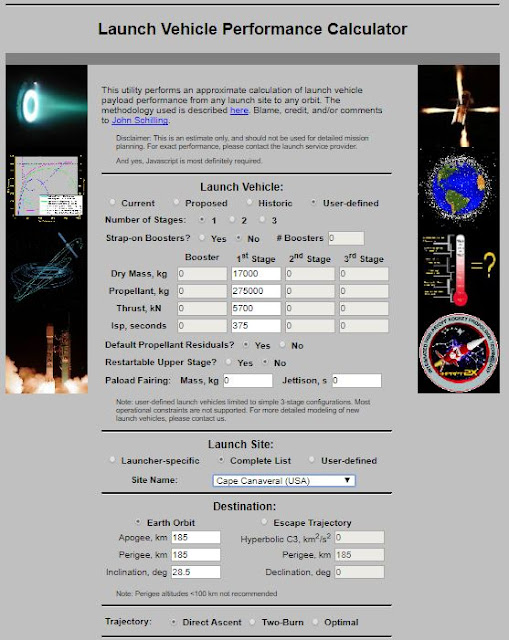

The input page looks like this:

Note there some quirks of this program you need to be aware of if you use it. First, always use the vacuum values for the Isp's and thrust numbers, since the program already takes into account the diminution at sea level. Second, always set the "Restartable Upper Stage" option to "No", rather than the default "Yes", otherwise the payload will be reduced. Third, always set the launch inclination to match the launch site latitude, otherwise the payload will be reduced. This is related to the fact that changing the orbital plane involves a delta-v cost. So for the Cape Canaveral launch site, the launch inclination should be set to 28.5 degrees.

Now, here's the result:

So a payload to LEO of 7 kg. And this with standard nozzles, no altitude compensation required.

Structure.

To save costs, I'm envisioning making the components as much "off-the-shelf" as possible. But among its standard products Cesaroni offers the Pro150 as the largest motor. So to get the larger second and first stages, we would have to combine multiple copies of this motor.

I could cluster them in parallel, but for the first stage that would be 16 of them, and you would have the problem of simultaneous ignition with that many motors.

So what I'm envisioning is take 4 copies of the Pro150 stacked vertically one on top of the other for the second stage, then cluster 4 of these second stage motors in parallel for the first stage.

The question is though about the vertical stacking is how much the thrust scales in this case. If for the solid motors the propellant burned from the bottom upwards, then the thrust would be the same as for a single motor, you would just get 4 times longer burn time.

But that's not how large solid motors work. Actually, they have a hollow region in the center so the propellant burns from the inside surface, proceeding outwards. In this case, you have a greater amount of propellant being burned per second because of the larger vertical surface area with the stacked segments. In fact, the thrust scales linearly with the number of segments.

By the way, the reason why I don't just also stack the first stage vertically, is because of the thinness of the rocket that would result. The Pro150 is about 3 feet long and 1/2 foot wide. If you stacked vertically 16 for the first stage, 4 for the second, and 1 for the third, that would be a rocket 63 feet high but only 1/2 foot wide, for a ratio of length to width of over 120 to 1.

This ratio of length to width is called the "fineness ratio". Rocket engineers don't like for it to be higher than about 20 to 1 because of the severe bending loads that would result. The upgraded version of the Falcon 9 has been noted for its long, skinny profile, and has a fineness ratio of about 20 to 1. The Scout solid rocket had a fineness ratio of about 24 to 1. Solid rockets can support a higher fineness ratio because their thicker walls can withstand higher loads. Still, 120 to 1 would very likely be too high.

So to avoid this I decided to form the first stage by clustering in parallel four copies of the second stage. Note here these four clustered motors arranged around the second stage will provide the full thrust for the first stage while the central second stage motor will not fire until the four clustered motors are jettisoned.

It would be possible though to get a single vertically stacked motor using multiple segments if the segments were shorter, resulting in a smaller rocket. For instance, there is a market for cubesats at only 1 kg mass to orbit. If you made the solid motor segments only about 1/2 foot long by cutting the Pro150 into 6 segments, you could take one of these smaller segments as the third stage, 4 segments for the second stage, and 16 segments for the third stage.

Cost.

The Cesaroni Pro150 retails for about $3,000 and in general the Cesaroni solids cost in the range of $100 per kg of the motor mass:

Cesaroni O8000 White Thunder Rocket Motor.

$3,099.95

Product Information

Specification

Brandname: Pro150 40960O8000-P Manufacturer: Cesaroni Technology

Man. Designation: 40960O8000-P CAR Designation: 40960 O8000-P

Test Date: 4/10/2008

Single-Use/Reload/Hybrid: Reloadable Motor Dimensions mm: 161.00 x 957.00 mm (6.34 x 37.68 in)

Loaded Weight: 32672.00 g (1143.52 oz) Total Impulse: 40960.00 Ns (9216.00 lb/s)

Propellant Weight: 18610.00 g (651.35 oz) Maximum Thrust: 8605.10 N (1936.15 lb)

Burnout Weight: 13478.00 g (471.73 oz) Avg Thrust: 8034.50 N (1807.76 lb)

Delays Tested: Plugged ISP: 224.40 s

Samples per second: 1000 Burntime: 5.12 s

https://www.csrocketry.com/rocket-motors/cesaroni/motors/pro-150/4g-40kns-reloads/cesaroni-o8000-white-thunder-rocket-motor.html

So take the cost of the third stage, derived from the Cesaroni Pro1050, as $3,000, and the second stage 4 times larger as $12,000, and the first stage larger by an additional factor of 4 as $48,000. So $63,000 for a smallsat launcher with a 7 kg payload to orbit.

Applications.

Several universities have created their cubesats and smallsats to be launched piggyback on large rockets such as the Falcon 9. However, the solid rocket launcher formed from essentially off the shelf components could be built by any interested university itself thus creating their own launcher and satellite.

Despite the small size of such satellites, and their low construction cost, the launch cost is still not cheap when sent piggyback. SpaceX for their latest incarnation of the Falcon 9 is charging about $60 million for a 20,000 kg payload to LEO, about $3,000 per kilo. But the price is much higher than that for small payloads that have to ride piggyback on launchers. For instance

Spaceflight Industries charges about $100,000 per kilo to book such flights. But a 1 kg cubesat launch would

only cost in range of $9,000 for one of these dedicated solid-rocket launchers.

The remaining entrants to the

Google Lunar X-Prize will have to pay expensive launch costs for their spacecraft to the Moon. But with the university teams using their own solid rocket launchers, the launch costs would be so cheap the teams could afford to make many attempts to win the lucrative $30 million prize to soft-land on the Moon, and many more teams could have remained in the race.

Also, both DARPA and the Army funded programs to develop such small dedicated launchers (liquid fueled), with their

ALASA and

SWORDS programs. But both their programs failed. They wanted to get about 25kg to 50kg to orbit for a launch cost of $1,000,000, about $20,000 to $40,000 per kilo. But the small size solid rockets will be able to beat this price, moreover will be more operationally responsive by using solid rockets. In a follow up post I'll discuss the payload can be more than doubled by using altitude compensation reducing the per kilo cost even further.

National security implications.

Recently, there has been some discussion on creating Ultra Low Cost Access to Space (ULCATS). See for instance this study:

FAST SPACE: LEVERAGING ULTRA LOW-COST SPACE ACCESS FOR 21ST CENTURY CHALLENGES.

http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/Portals/10/Research/documents/Space/Fast%20Space_Public_2017.pdf

Most of the discussion has been about how this would improve U.S. capabilities. But surprisingly little has been about what are the national security implications of any university world-wide and many knowledgeable amateur groups world-wide launching their own rockets to orbit.

To prepare for this, which will be here like tomorrow, this discussion must begin now.

Bob Clark

Note: thanks to former aerospace engineer and math professor GW Johnson for helpful discussion on this topic on the NewMars.com forum:

Amateur solid-fueled rockets to *orbital* space?

http://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.php?id=7763